Although loss aversion is an easy concept to grasp, it is much harder to overcome in portfolio management, which is why a clearly defined, proven investment process is invaluable.”

It seems surprising we are only in June—it feels more like December, given how many “lives” the market has already experienced this year. This spring, many clients asked how we navigated the post-Liberation Day sell-off—whether we bought and sold a great deal or trusted our long-term theses enough to wait it out. The answer lies somewhere in between.

To bolster our buy-and-sell decisions, the team used a portfolio exercise designed to temper behavioral bias in the face of market volatility, focused on avoiding loss aversion and the reward-to-risk potential of the individual securities.

Avoiding loss aversion

Our team has long believed that all investors are subject to behavioral biases. To counter this, we have developed a library of creative portfolio exercises designed to minimize these biases. They also serve to help the team think beyond the day-to-day noise and focus longer term on behalf of our clients.

In early April, we performed an exercise evaluating the reward-to-risk level of the individual companies within our portfolios, to help avoid loss aversion. Numerous studies show that not letting one’s emotions get in the way when something is going against you (in our case, a specific company), will typically help in the long term. One relevant study published in Psychological Science1 supports this—demonstrating that loss aversion changes based on recent experience.

Emotional bias can undermine decision-making

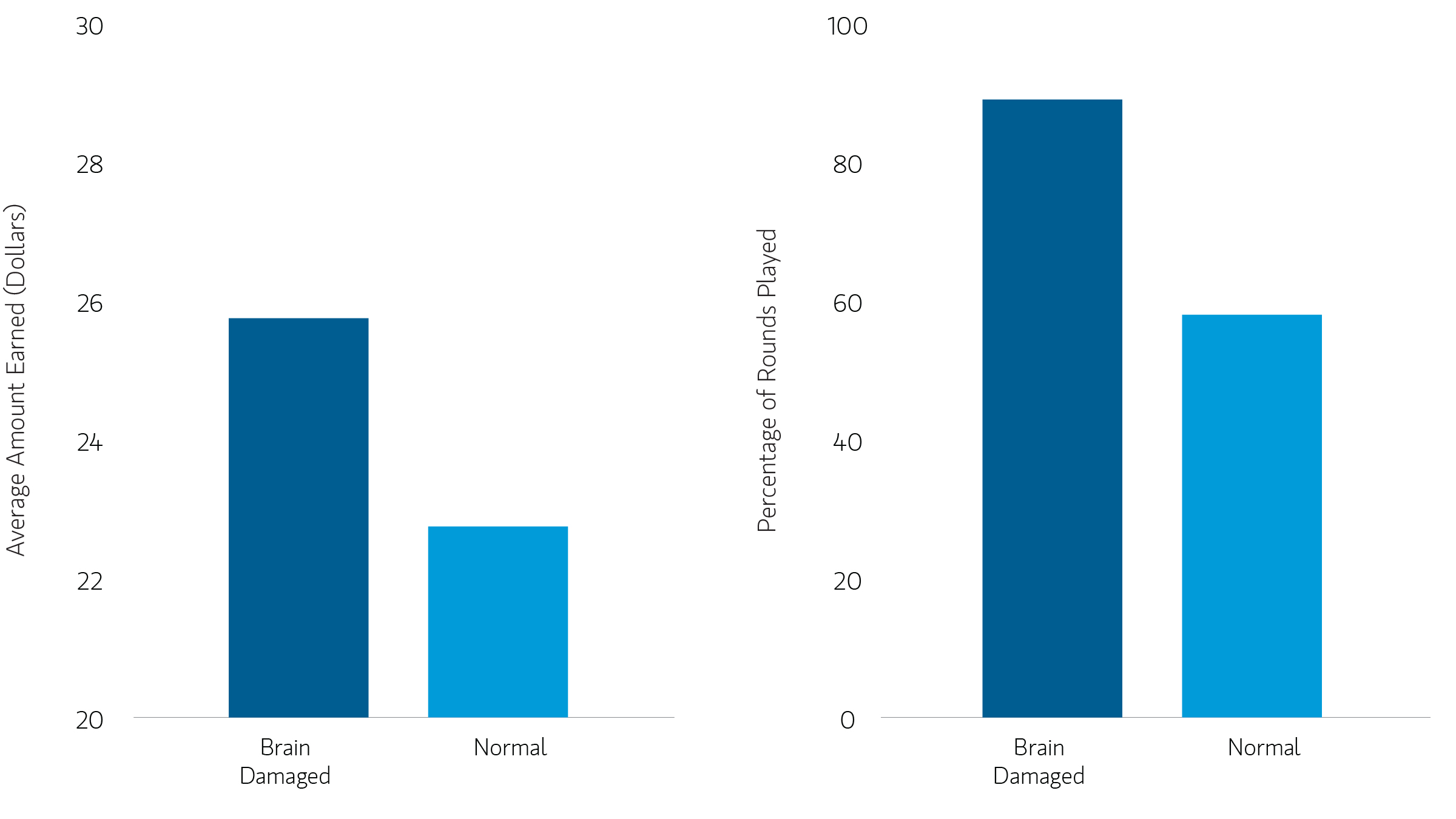

The Psychological Science study highlighted that when emotions guide decision-making, it can lead to suboptimal choices, particularly in situations involving uncertainty. In this study, scientists compared the decisions of “brain impaired” people with lesions on the part of the brain that controls emotions, and “normal” people who did not have these lesions. Participants in both groups were asked to make 20 rounds of investment decisions. In each round, they were given $1.00 and had to decide whether to keep or “play again” and invest it. Although the odds were explicitly stacked in favor of the normal participants (i.e., positive expected value), the findings revealed that the brain-damaged participants ultimately made better decisions and more money than the normal participants.

So-called “normal” people stopped playing when they lost (or won) on an emotional fear of loss, ultimately believing past results influence future results. This hindered their ability to maximize profits in the long run.2

Strategy over sentiment

Although loss aversion is an easy concept to grasp, it is much harder to overcome in portfolio management, which is why a clearly defined, proven investment process is invaluable. In our case, this means consistently purchasing companies that exhibit a high free-cash-flow profile, low leverage, and solid return on invested capital—important attributes proven to generate higher alpha over time.3

While we routinely evaluate reward-to-risk in our portfolio companies, in the team’s portfolio exercise, we applied that analysis through the lens of recent market volatility. Companies were separated into two groups: those trading at or near our analysts’ “bear case” within their weighted price potential, and those at or near their “bull” or “base” case—even after the recent downturn. For companies near their bull or base case, we asked analysts to consider whether they would trim the position size, exit it entirely, or if something had changed in the company’s weighted price potential framework. In that case, they would have to re-present the company to the team.

Likewise, for names at or near our bear cases, we asked analysts whether the bear case still held. If it did, and we believed the fundamental thesis remained valid and still achievable despite short-term, macroeconomic noise, then we concluded we should add to the position, despite any uncomfortable emotions around that decision.

Bottom line: We believe sticking to our time-tested process during volatile times is essential, as it helps ensure we consistently put capital behind companies where we see the greatest reward-to-risk potential.

Featured Insights